Travels With Cody

Text and photos by Dick Gibson

December 1999—January 2000

Canine comments by Cody (R.I.P.; 1998-2011)

Rediscovering Winter Wonder

Once in a lifetime, if one is lucky,

one so merges with sunlight and air

and running water that whole eons.... might pass

in a single afternoon without discomfort.

— Loren Eiseley, The Immense Journey

|

Like John Steinbeck in Travels With Charley, I am in love with Montana. Like many of you, I've been to lots of places—Yosemite, Glacier Park, the Grand Canyon, Milford Sound, Canyonlands—where the eye and brain are saturated with the wonder and amazement to be found with every glance. But I've never lived in such a place before. Daily the scene changes, often hourly, sometimes from minute to minute. Cody and I want to share some of those minutes—all found by walking no more than two miles from the Field Station.

Rays exploded downward from the sun's low ride above Cataract Peak, as the star gave thought to setting. Overhead, the warm summer-blue sky at the station, with fleecy clouds, belied the threat of snow that looked like a dust storm twirling up the valley. Who would know it was January? Rays exploded downward from the sun's low ride above Cataract Peak, as the star gave thought to setting. Overhead, the warm summer-blue sky at the station, with fleecy clouds, belied the threat of snow that looked like a dust storm twirling up the valley. Who would know it was January?

Walking up the South Boulder Road gives the best views toward the upper valley—and an ever-changing panorama. In the morning after a fluffy snowfall, it is a fantasyland of sparkles. Few vehicles have disturbed the road surface, so the tracks are just another pattern drawing you into the landscape. Cody waits, either out of loyalty or fear of being left alone. He rarely follows the simple paths I take (often just along the road). His excursions are more like Billy's in The Family Circus—zigging, zagging, crossing, curving, veering, as smells or sights or sounds drive him to explore every spot that exists. Virtually all depressions in the snow, be they real animal prints or not, merit a nose check. If the results of the analysis are interesting, he may be off along a line of tracks as if he were a hunter! Maybe he is! Walking up the South Boulder Road gives the best views toward the upper valley—and an ever-changing panorama. In the morning after a fluffy snowfall, it is a fantasyland of sparkles. Few vehicles have disturbed the road surface, so the tracks are just another pattern drawing you into the landscape. Cody waits, either out of loyalty or fear of being left alone. He rarely follows the simple paths I take (often just along the road). His excursions are more like Billy's in The Family Circus—zigging, zagging, crossing, curving, veering, as smells or sights or sounds drive him to explore every spot that exists. Virtually all depressions in the snow, be they real animal prints or not, merit a nose check. If the results of the analysis are interesting, he may be off along a line of tracks as if he were a hunter! Maybe he is!

The tatters of the storm may remain as fogs and blusters of ice crystals, sometimes obscuring—but not sullying—the near or distant scene. The tatters of the storm may remain as fogs and blusters of ice crystals, sometimes obscuring—but not sullying—the near or distant scene.

Something soft and wild and free,

something that whispered to the ear on the pillow,

lightened the heart, softly, softly picked the lock,

slid the bolts, and released the prisoned spirit of man

into the wind, into the blue and gold,

into the morning, into the morning!

— Willa Cather

|

The interplay of cloud, sun, and earth is a loud expression of renewal, punctuated by the screeee! of a magpie or the raucous caw of a raven. If the wind is calm, you will hear the cascade of the river if you are near enough. But if the wind chooses to exert itself, it becomes a Giant in the Earth, the dominant entity, the only thing that gets your attention. It controls the meanings of words like “warm” and “comfortable.” The wind is only rarely absent completely. Sometimes it teases, a soft backdrop to existence, a plaything in the firs, but more often it roars, seeming to shake the whole hillside in anger, or apathy. The wind at night, under a lowering, cloudy, starless sky, can feel like an animal, a huge beast tearing at the trees. It's not inimical, not malevolent—just profoundly uncaring. It's one of Nature's many 600-pound gorillas.

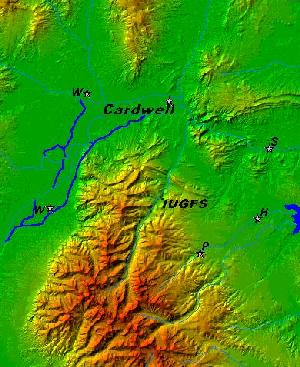

The South Boulder River

From space, the river looks remarkably straight. Its northnortheast trend is the most prominent gash in the Tobacco Roots—in fact, it once gave its name to the range. After the wind, the river is the most audible presence at the Field Station. It's always there, like a friend. I like to think about the boulders in the riverbed and how they are ultimately on their way to the Gulf of Mexico, to add to the deltaic pile of Mississippi mud—but not this year, not this millennium! From space, the river looks remarkably straight. Its northnortheast trend is the most prominent gash in the Tobacco Roots—in fact, it once gave its name to the range. After the wind, the river is the most audible presence at the Field Station. It's always there, like a friend. I like to think about the boulders in the riverbed and how they are ultimately on their way to the Gulf of Mexico, to add to the deltaic pile of Mississippi mud—but not this year, not this millennium!

While linear in general, the South Boulder is intricately convoluted in detail, especially in winter. Shelves of ice form temporary banks that support layers of snow, making sharp, serrate edges against the black water. Smoothly curving meanders lend a Zen-like peace to certain reaches of the river, pacifying its loud rush to lower lands. The snow that caps the boulders in the stream, like white mushrooms in dark soil, comes and goes from day to day. Shelves of ice form temporary banks that support layers of snow, making sharp, serrate edges against the black water. Smoothly curving meanders lend a Zen-like peace to certain reaches of the river, pacifying its loud rush to lower lands. The snow that caps the boulders in the stream, like white mushrooms in dark soil, comes and goes from day to day.

Near the water, icecaps develop over and around the rocks, with fragile skirts of transparent ice. On warm days, inevitably, the enveloping ice-sheath weakens and falls away, to become flotsam further downstream until it rejoins the liquid flow. Are they the more beautiful because they are ephemeral? Or is that how all beauty is? Near the water, icecaps develop over and around the rocks, with fragile skirts of transparent ice. On warm days, inevitably, the enveloping ice-sheath weakens and falls away, to become flotsam further downstream until it rejoins the liquid flow. Are they the more beautiful because they are ephemeral? Or is that how all beauty is?

During the Fall, Cody had become accustomed to retrieving sticks tossed into the water, but he's not stupid—he knows cold when he feels it! But that does not keep him from exploring the river bank, always looking expectantly for me to throw something, anything, in the stream. He slows down more along the stream than anywhere. Below the house, where there is a big  S-curve and a deep hole, and large piles of flotsam and jetsam and many-trunked briars and trees, he can spend 10 minutes investigating a single pile of logs and debris. Maybe there are muskrats or whatever in there—he seems interested enough. S-curve and a deep hole, and large piles of flotsam and jetsam and many-trunked briars and trees, he can spend 10 minutes investigating a single pile of logs and debris. Maybe there are muskrats or whatever in there—he seems interested enough.

A small tributary without the power to keep from freezing turns into a tiny frozen Niagara near the bridge. The surface appears to have developed like flowstone in a cave, with frozen ripples as each pulse of meltwater makes its way somehow further downstream. It traps the shucks of summer flowers in stillborn waves that reflect the setting sun.

We went down the South Boulder Road one morning during a heavy snowstorm. Cody may not know about magical and mystical and beautiful, but he seems to be the most invigorated when the snow is falling. He takes energy from the swirling flakes, maybe, and I take energy from his excitement and joy. Quite apart from his happy-meter (his tail), there is absolutely no question but that he smiles when he's having a great time. I used to think that his bullet-like gallops We went down the South Boulder Road one morning during a heavy snowstorm. Cody may not know about magical and mystical and beautiful, but he seems to be the most invigorated when the snow is falling. He takes energy from the swirling flakes, maybe, and I take energy from his excitement and joy. Quite apart from his happy-meter (his tail), there is absolutely no question but that he smiles when he's having a great time. I used to think that his bullet-like gallops hither and yon were when he caught a scent of something, but I'm sure he also does it purely for the joy of running. He loves to run! And he's a happy dog most of the time. hither and yon were when he caught a scent of something, but I'm sure he also does it purely for the joy of running. He loves to run! And he's a happy dog most of the time.

The Pony Road

How can I describe the Pony Road? Just a rough, somtimes impassible dirt road in the foothills of the Tobacco Roots—but also a place of wonder and peace and astonishment that stops me in my tracks, makes me give up trying to refrain from saying "Oh, Wow!" It's a place that changes so much, so often, that I cannot imagine becoming tired of exploring it. I know its curves and where the grades are, some of its outcrops, a few of its stands of trees—but there is a universe of light and color and life and events to experience there. How can I describe the Pony Road? Just a rough, somtimes impassible dirt road in the foothills of the Tobacco Roots—but also a place of wonder and peace and astonishment that stops me in my tracks, makes me give up trying to refrain from saying "Oh, Wow!" It's a place that changes so much, so often, that I cannot imagine becoming tired of exploring it. I know its curves and where the grades are, some of its outcrops, a few of its stands of trees—but there is a universe of light and color and life and events to experience there.

Two days after the eight-inch snow of early January, under bright sun for the first time in three or four days, Cody and I set out around noon.

Rise free from care before the dawn,

and seek adventures. Let the noon find thee by other lakes,

and the night overtake thee everywhere at home.

There are no larger fields than these,

no worthier games than may here be played....

Grow wild according to thy nature,

like these sedges and brakes,

which will never become English hay.

— Thoreau

|

Cody likes the Pony Road because it is so open, he can range far and wide but still check up on where I am. He'll be high on the slope north of the road, and 30 seconds later (it seems) he's a quarter-mile away, across Carmichael Creek and on the hillside to the south. If you keep your eye on him, you'll see that despite his mad dashes on trails and otherwise, every so often his head pops us as he stops to look back to see what little progress I may have made—and from his viewpoint, my progress is probably minimal, even when I don't stop to make pictures. "WHAT? He's only gone that far? Come ON!"

We found right away that we were not alone. Every 50 or 60 feet along the roadway, trails of tiny feet revealed the homes of field mice or voles along the bank on the north side of the road. Smart critters, every one seemed to have chosen a southern exposure for its nest in the rocks and earth. We found right away that we were not alone. Every 50 or 60 feet along the roadway, trails of tiny feet revealed the homes of field mice or voles along the bank on the north side of the road. Smart critters, every one seemed to have chosen a southern exposure for its nest in the rocks and earth.  Some had come straight out onto the snow, while others tunneled a few inches before surfacing. The tunnels were no more than ¾" in diameter, but the trails ranged from inches to tens of yards long. Apparently some mice are more venturesome than others—or maybe just hungrier. Some had come straight out onto the snow, while others tunneled a few inches before surfacing. The tunnels were no more than ¾" in diameter, but the trails ranged from inches to tens of yards long. Apparently some mice are more venturesome than others—or maybe just hungrier.

Before long we encountered the beaten paths followed by deer. Almost all of them spent very little time on the road, and most of the trails crossed it at a high angle. One exception was the track of a lone animal—not a deer. It had a track similar to Cody's paws, but just  slightly smaller, and the span of the legs was a bit less than Cody's as well, so I suspect a coyote. He walked on the road for a long time before heading into the dark stand of trees south of the creek. Ike Gilstrap told me that his son Todd had seen a mountain lion up at the Pony Pass, and that loggers out hunting had spied two up Brownback trail, but I don't think these tracks were those of a cougar. slightly smaller, and the span of the legs was a bit less than Cody's as well, so I suspect a coyote. He walked on the road for a long time before heading into the dark stand of trees south of the creek. Ike Gilstrap told me that his son Todd had seen a mountain lion up at the Pony Pass, and that loggers out hunting had spied two up Brownback trail, but I don't think these tracks were those of a cougar.

Past the sharp bend in Carmichael Creek to the southeast, we ascended the road along what I've started calling Pony Pass Creek, the unnamed tributary of Carmichael that the road follows most of the way to the pass. The stream was frozen over and snow-covered in most places, but in some wider pools, dammed by deadfall of aspen, black transparent ice was encrusted by large white sprays of ice crystals. White chrysanthemums or stilbite sheafs from the Deccan traps of India could not be more wonderful. Past the sharp bend in Carmichael Creek to the southeast, we ascended the road along what I've started calling Pony Pass Creek, the unnamed tributary of Carmichael that the road follows most of the way to the pass. The stream was frozen over and snow-covered in most places, but in some wider pools, dammed by deadfall of aspen, black transparent ice was encrusted by large white sprays of ice crystals. White chrysanthemums or stilbite sheafs from the Deccan traps of India could not be more wonderful.

The aspen groves up Pony Pass Creek provide a break from wonders of ice. Some of the trees are so bare in their lower trunks that they seem like the baobab tree of Africa, with its roots in the air. The fallen logs provided Cody with a weath of nooks to explore, but as far as I could tell he did not discover anything mammalian. The aspen groves up Pony Pass Creek provide a break from wonders of ice. Some of the trees are so bare in their lower trunks that they seem like the baobab tree of Africa, with its roots in the air. The fallen logs provided Cody with a weath of nooks to explore, but as far as I could tell he did not discover anything mammalian.

There's a stand of thistle skeletons there, too. Thistles amaze me; they strike me as among the most alien looking of plants, and in their winter dryness they are even stranger. There's a stand of thistle skeletons there, too. Thistles amaze me; they strike me as among the most alien looking of plants, and in their winter dryness they are even stranger.

As we turned toward the Station, the light breeze began to puff up into occasional strong gusts. But it was far worse up on Brownback, where a small snow tornado exploded, to twist and cavort on the north slope under a clear blue sky. The winds had been tossing snow around on the peaks all day, and I had seen "snow-devils" even down on the Field Station grounds on earlier occasions, but this was a pretty big one. The photo only suggests its sudden power, yet another captivating "Oh Wow!" And yet another transitory, momentary item in a long list of constant changes that shape the minutes and days here.

Closer to home

The trees on the hill east of the Field Station hide many deer, to judge from their tracks (deer tracks, not tree tracks). One old giant Douglas fir may have been ripped by lightning, but it still seemed dynamic and alive. It is near the edge of the dense stand due east of the Lodge, and some of its neighbors are of similar size. One monarch lived 157 years before the loggers came in 1993; only the stump remains. The trees on the hill east of the Field Station hide many deer, to judge from their tracks (deer tracks, not tree tracks). One old giant Douglas fir may have been ripped by lightning, but it still seemed dynamic and alive. It is near the edge of the dense stand due east of the Lodge, and some of its neighbors are of similar size. One monarch lived 157 years before the loggers came in 1993; only the stump remains.  The brow of the hill gives a view of the valley to the north, with distant snow-capped Elkhorn and Crow Peaks on the horizon. From here, or further north along the Logging Road, the river is a faraway rustle behind the trees. The rocks take more of my attention, because in places here the garnetite is common. Lichen-encrusted gneiss is almost as interesting, however. The brow of the hill gives a view of the valley to the north, with distant snow-capped Elkhorn and Crow Peaks on the horizon. From here, or further north along the Logging Road, the river is a faraway rustle behind the trees. The rocks take more of my attention, because in places here the garnetite is common. Lichen-encrusted gneiss is almost as interesting, however.

The surface of the snow has gone from unbelievable miraculous forests of bladed mirrors to spherical ice like you get in a snow cone (or in lower reaches of ski runs in April), and on to a crusty, almost scoriaceous surface that is sharp-edged. Cody learned rapidly that he can no longer scoop up a mouthful of fluff, and now he attacks a mound and bites off chunks. It sounds like he's eating styrofoam.

None of these expeditions seemed to tire Cody noticeably. After Tom and Aaron Howald, Cody, and I hiked up Brownback Gulch and back via the draw to the north—possibly as much as 4 miles for the humans, but easily double that for Cody—he was visibly tired. None of these expeditions seemed to tire Cody noticeably. After Tom and Aaron Howald, Cody, and I hiked up Brownback Gulch and back via the draw to the north—possibly as much as 4 miles for the humans, but easily double that for Cody—he was visibly tired.  Usually he'll submit to the routine burr-removal, then he's rarin' to go again. Even after dark, he'd rather go outside than anything, no matter if it is a blizzard, 5° above zero, whatever. It's very difficult for me to refrain from anthropomorphizing, but I really think he has as good a time as I do. Usually he'll submit to the routine burr-removal, then he's rarin' to go again. Even after dark, he'd rather go outside than anything, no matter if it is a blizzard, 5° above zero, whatever. It's very difficult for me to refrain from anthropomorphizing, but I really think he has as good a time as I do.

I get my sensations mainly from sight and sound and feel, but he has a couple more senses that are pretty meaningful and presumably contribute to his enjoyment of his world. He certainly employs his sense of smell enough!

Skating away,

on the thin ice

of a new day...

— Jethro Tull

|

Each day is its own reward, each glance a new filling of the treasure chests of the mind. Miniature crystal forests without limit, tiny records of events in small creatures' lives, big trees fallen or chopped or standing tall, these are all part of a huge Zen garden that is perhaps too delightful for proper meditation. Each day is its own reward, each glance a new filling of the treasure chests of the mind. Miniature crystal forests without limit, tiny records of events in small creatures' lives, big trees fallen or chopped or standing tall, these are all part of a huge Zen garden that is perhaps too delightful for proper meditation.

The wind is the rake for this winter garden, as it redraws the sastrugi, the regular etchings in the snow. The snow changes daily in texture, surface structure, cohesiveness, and density, and I can begin to appreciate the Inuit's 57 words for snow—or was that Heinz? No matter, the variety is not finite, nor sharply categorized, but smoothly and continually and amazingly altering into something that is not quite what it was. The wind is the rake for this winter garden, as it redraws the sastrugi, the regular etchings in the snow. The snow changes daily in texture, surface structure, cohesiveness, and density, and I can begin to appreciate the Inuit's 57 words for snow—or was that Heinz? No matter, the variety is not finite, nor sharply categorized, but smoothly and continually and amazingly altering into something that is not quite what it was. Kind of like life. And isn't being amazed, learning, discovering, a vital part of being alive? I think Cody would agree.

There's nothing constant in the Universe, All ebb and flow,

and every shape that's born bears in its womb the seeds of change.

—Ovid (56-117 A.D.)

©2000 Richard I. Gibson

Back to Expeditions Page

|